A retired orchestra conductor is on holiday with his daughter and his film director best friend in the Alps when he receives an invitation from Queen Elizabeth II to perform for Prince Philip’s birthday.

In Youth Paolo Sorrentino’s visual whimsy is bittersweet. It’s thought provoking, but feels like a put on. But it certainly works to a degree. It’s a spectacle of technical acumen and artful exploits. Terrence Malick, eat your heart out. Sorrentino’s not a pure stylist. While film is a visual medium—I have a friend who just loves to remind me of this for some reason—if you listen to Sorrentino’s Youth, you get a better idea of why it feels so empty.

Sorrentino sets off a nuclear bomb of personal philosophies, much like in his previous film, The Great Beauty, which I personally found to be a painful experience to sit through. Whether it’s the super smug wisdom of a hip nightlife living Mr. Magoo lookalike named Jep, or the rank-and-file revelations of a pair of great artists entering their twilight in Youth, the effect is almost exactly the same—suffocation by way of someone else’s idealism.

Michael Caine stars as Fred Ballinger, a retired orchestra conductor famous the world over for his “Simple Songs.” Fred is embarrassed by what he views as lackluster street cred in the classical music scene, though the Queen of England is hunting him down to play a concert for her, and the French (as in, the entire French nation) are demanding his memoirs. Fred is on vacation with his daughter/assistant, Lena (Rachel Weisz), at a resort in the Swiss Alps. Lena has a problem with how her dad treats her mom, but Fred just misses his wife, and it’s only later that any of this contradictory and vague narrative thread ties together to something coherent but unsatisfying. He is staying with his best buddy, Mick (Harvey Keitel), who is there to finish a script for his next movie, which he plans to be his magnum opus (it’s title: “Life’s Last Day”). Mick and his team of screenwriters squawk with the snippy ferocity of high schoolers with good grades. Fred and Mick stroll around the Alps shooting the breeze about old girlfriends, urination complications, and deriding the resident Buddhist monk who has yet to levitate in the twenty years Fred has frequented the place. You can guess whether or not the monk levitates by film’s end. Every image you see matches up with some inane snippet of dialogue, making it hard to appreciate whatever it is Sorrentino would rather us focus on visually.

Pop stars are compared to prostitutes, and a Miss Universe contestant gets to stand tall in the face of scrutiny over her aspirations to be an actor–are any of these stereotypical juxtapositions interesting to anyone anymore? Lena is dumped by her handsome boyfriend for not being good in bed, but finds new love in the most “unlikely” place—a bearded, only decent looking mountain climber. A young actor (played with the most annoying affectation by Paul Dano) is running away from his early success as a big budget superhero named Mr. Q, and I couldn’t help but have posttraumatic flashbacks to all the things I disliked about Inarritu’s Birdman—another film, an Oscar winner like Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty, that seemed to fool audiences into buying its whiny, cranky, glib perspectives on life, culture, and the arts as worthwhile intellectual rumination. “Blowhard” is a strong term, and yet it’s the first thing that springs to mind when I think of these hulking manifestos by filmmakers with lots of ambition, but not enough imagination to make their worldviews and their craft come together in harmony. Every scene, every shot in Youth is connected to some kind of generalized philosophy, or moral, or life lesson. It’s like every childless uncle in the world helped to write the script in hopes of someone young taking heed of their advice.

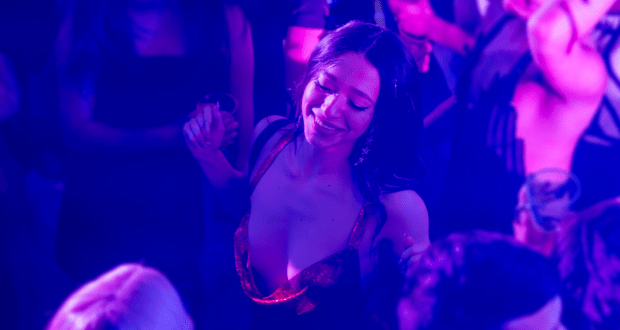

Sorrentino’s style actually is interesting. His slow moving camera work, eye for black comedy, and sentimental, dreamlike absurdity works well enough. Watching Michael Caine conduct a field of cows wearing cowbells is on the silly side, but it’s also in line with Sorrentino’s full throttle brand of emotional art house sensationalism, and these little nuggets of visual stimulation are at least something to stay awake for. There isn’t enough style to drown out the purposefully stringy narrative or the many other moments of unabashed pontification. And there are provocations, though they seem more like the firing of a flare gun in hopes of bringing attention back down to earth. Whether it’s the bull in a china shop cameo of a Jane Fonda, or someone jumping out of a window to their overtly dramatic death, Sorrentino throws haymakers hoping one will land, and that the impact will feel like substance. But the one “truth” I realized after taking in Youth was that I had wasted some of my own while watching it.

-

Acting - 7.5/10

7.5/10

-

Cinematography - 7/10

7/10

-

Plot/Screenplay - 5/10

5/10

-

Setting/Theme - 3/10

3/10

-

Buyability - 3/10

3/10

-

Recyclability - 3/10

3/10