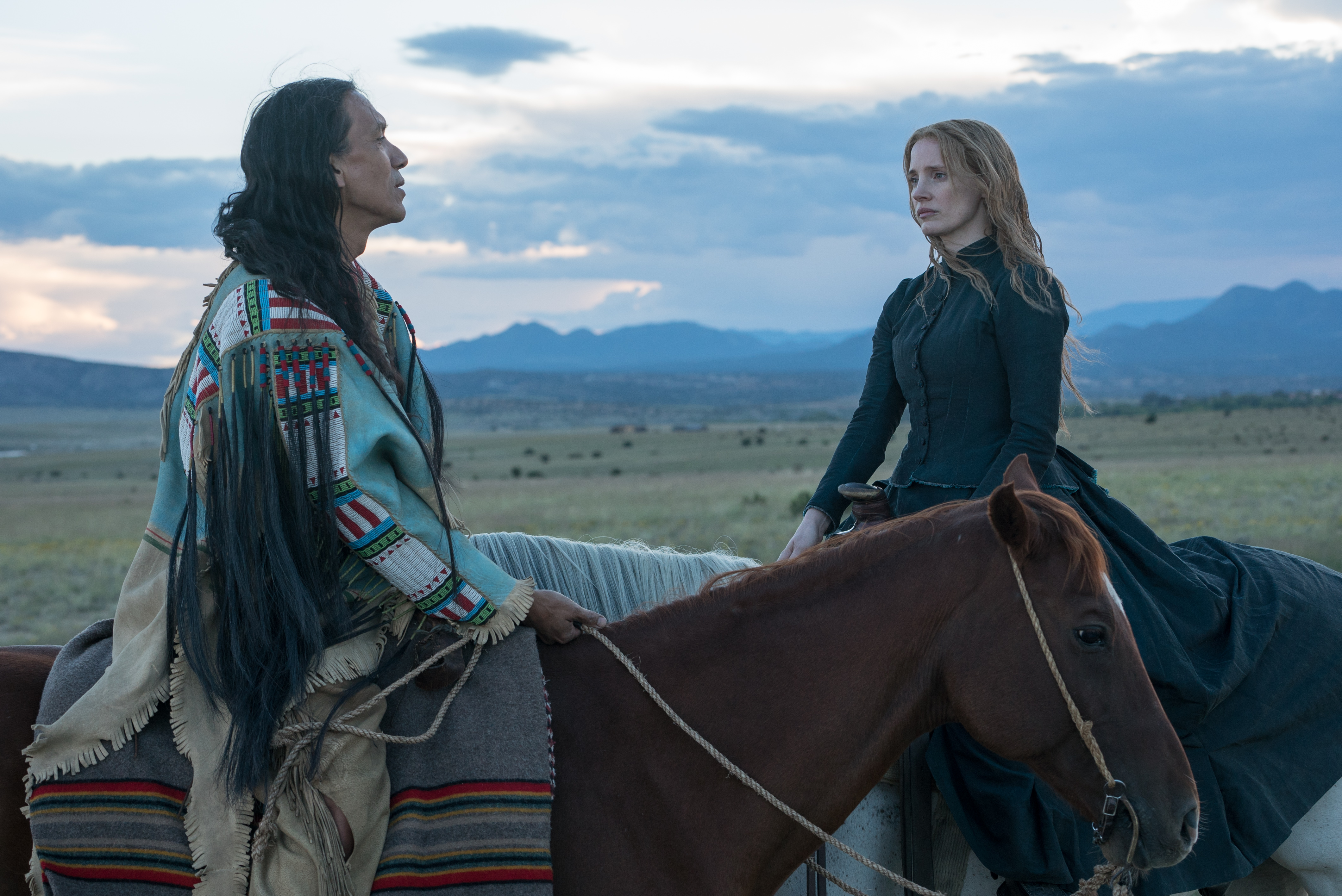

In Woman Walks Ahead, director Susanna White and star Jessica Chastain have taken a true story about the American West and created an elegiac meditation on the environment and a wrenching commentary on social injustice. Chastain stars as Catherine Weldon, a stubborn widow who traveled from New York to North Dakota in the 1880’s to paint a portrait of the legendary Lakota holy man from the Lakota tribe, Chief Sitting Bull (Michael Greyeyes). Throughout her journey as a woman she is treated dismissively and contemptuously but persists in her goal to paint the noble leader who she discovers has turned into a farmer.

Woman Walks Ahead looks at the American West with a feminine gaze that is unusual in the “Cowboys and Indian” genre. At the same time the movie’s main focus is on one of the darkest periods of American history, during which Native Americans were robbed of their land and their culture nearly erased. This is a genocide rarely taught in high school history books. Throughout the film there is the ominous portending of the Massacre at Wounded Knee which adds another layer of tragedy to the events depicted in the film. (The cast includes Sam Rockwell, Ciarán Hinds and Bill Camp.)

“Woman Walks Alone,” which premiered at the Toronto Film Festival, celebrated its U.S. premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival recently. I was on the red carpet and spoke briefly to English director Susanna White about her efforts to maintain historical authenticity and what it was like looking at the West through a feminine lens:

Susanna White/Paula Schwartz photo

As a Brit do you think you have a unique perspective on this particularly horrific part of American history that an American filmmaker might not?

Susanna White: I am British. But I think that we bear some responsibility for it too. We did terrible things. We gave the Native Americans blankets infected with small pox, which was a very deliberate act of genocide. We have a lot to answer for in all of this.

What inspired you to tell the little known story of Catherine Weldon and Sitting Bull?

SW: I’ve always been interested in films made by outsiders, whether that is “Paris, Texas” or “Lost in Translation.” I think there’s something to be said about coming into a situation as an outsider. The idea really came about because of the writer, Steven Knight (“Dirty Pretty Things,” “Eastern Promises,” who came up with the idea maybe 14 years ago. He found this footnote in the history books about Catherine Weldon and he’s given her a voice. So it’s a story about two disenfranchised people. Catherine Weldon is our eyes and ears in just seeing the demeaning ways that the issues of Native-American land rights and Sitting Bull and the Lakota community were treated. I’m very glad to have the chance to bring it to the screen.

How did you maintain conveying the fidelity of the Lakota Native-American culture throughout Woman Walks Ahead?

SW: There were lots of things (we did). We had them speak their own language, which is now virtually a dead language. We worked with a remarkable man called Ben Black Bear who’s trying to keep the language alive, so late sections of the film are in Lakota. One of the things which the white settlers did was to make it illegal for the Lakota people to wear traditional dress or carry out acts of worship in the traditional way. And we went back to documentary photographs of the time where you see that lots of Native Americans were wearing Western dress. Well that’s not what you traditionally see in Westerns. So through the film I worked with our costume designer, Stephanie Collie, starting out with the first time Catherine meets Sitting Bull he’s dressed in Western clothes. And then gradually, as they take up more and more of the campaign for their land, you see the Native clothes coming back and they’re very, very beautiful. And I was so struck in the research at the art and the craftsmanship. And it was really a terrible thing that they were forced to destroy those artifacts.

How important was research in maintaining authenticity?

SW: Very, very important to me. I mean there’s been some conflation of historical facts to make it work as a film narrative but basically it was based on an essential truth about what happened to these people, that their culture was wiped out and more and more of their land was taken away and they were forced out of their traditions. And there’s a strong environmental message to the film, which is one of the remarkable things about the people, which was traditionally they lived in harmony with nature. They followed the buffalo herds… and then as the settlers came in, then the buffalo were wiped out. They were forced to live on land where you couldn’t grow things. It wasn’t fertile land, so another way of controlling the population was by forcing them to live on hand outs from the army with rations and then the threat of the rations being withdrawn was farther devastation which is what the government wanted, so it’s a complex story but I think it’s an important environmental lessons that we can learn from because the planet’s in a perilous state at the moment.

How did this movie come about?

SW: I was given the script by my agent about three years ago and I fell in love with it. I grew up on Westerns but I think this Western, told through a female gaze was a very particular take on that. And then the story of this extraordinary, brave woman from 1890’s Brooklyn who was trying to be a painter at a time women’s weren’t allowed to paint, she set out on this extraordinary journey, so shining a torch on this episode of history through her gaze was key. She’s our eyes and ears into this world.

When you read the story what was it about Sitting Bull that inspired you to portray him so sympathetically?

SW: I loved that Sitting Bull was so sophisticated, such an intellectual. He’s got a great sense of humor. He’s a real person, a large, charismatic figure and that was irresistible to bring to the screen.

How did Jessica Chastain become involved?

SW: When we were looking to cast Catherine she was absolutely top of my list. I think she’s so close to who Catherine Weldon was. She’s very outspoken politically herself. She’s such a consummate actress, so skilled, and someone at the top of her game and it was thrilling to have the culmination of her, Michael Greyeyes, Sam Rockwell.

You’ve been doing a lot of television work recently set in contemporary times like “Billions.” Did you find a period piece like this very challenging?

SW: I’ve done some period drama before like “Bleak House” and “Jane Eyre.” But I’m a great believer that it’s an accident when our particular piece of DNA arrives on the planet. You know I could have been born in Medieval times, I could have been born in Victorian times, I could have been born in the 1960’s. I think it’s accident when you arrive, so all my work is about trying to just tell the story of individuals and make their characters real and truthful and my first principal is always just making the scenes real for the actors as a way of telling the story.