Media depictions of substance use are often far removed from the reality of dependence and addiction, rarely reflecting the actual experience of those suffering from this condition. Media images can reinforce negative stereotypes and obscure effective pathways to recovery. Here are some common media misconceptions about addiction and recovery:

Myth #1: You have to hit “rock bottom” before you can begin recovery.

The myth: The “hitting rock bottom” metaphor is commonly used in Alcoholics Anonymous/Narcotics Anonymous (AA/NA) to describe the moment when a person finds themselves facing such dire consequences of their addiction that they finally recognize the need to make a change. In the movie 28 days, Sandra Bullock’s inebriated character topples her sister’s wedding cake before entering the rehabilitation that eventually frees her from her addiction; A Star Is Born shows Bradley Cooper’s drunken character urinating onstage during an awards show to the horror of his wife and the audience, after which he finally enters a residential facility.

The truth: While it can be a relatable concept, reaching a state of total desperation is neither universal nor necessary to seek treatment for substance use disorders. Moreover, the disease trajectory of a downward slope to rock bottom, followed by a steady upward recovery, is not backed by science; instead, the science of addiction supports a chronic disease model, where periods of improvement are punctuated by worsening disease or relapse.

Treatment can be effective at any stage of a substance use disorder. The best time to seek treatment is as soon as someone realizes there is a problem, such as when a typical prescription for pain medications fails to last as long as it should, resulting in rebound pain and withdrawals when medication runs out. However, individuals along any part of the opioid use disorder spectrum deserve standard-of-care treatment, even after severe consequences arise, like overdoses, infections from injecting drugs, and impairment of life activities.

Myth #2: Shame and punishment are gateways to healing.

The myth: People with substance use disorders respond well to aggressive confrontation, which open’s the individual’s mind to their failings and facilitates a clear pathway to recovery. The A&E show Intervention is perhaps the most current example of this media myth, but it follows the example set as far back as 1978’s “Scared Straight” documentary that used fear tactics to encourage at-risk teenagers to improve their behavior.

The truth: According to the fifth Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM5), criteria for substance use disorders includes “continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by opioids” and “recurrent use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.” These criteria define addiction as a condition that is not responsive to negative consequences; it then stands to reason that shame and other punitive approaches are not effective approaches to curing people of the disease.

This fundamental fact calls into question the use of incarceration as a response to drug use; while law-enforcement responses to substance use might be well-meaning, mass imprisonment does less to inspire individuals toward recovery than to traumatize them, further pushing them toward drug use and negative behavior.

While they may be well-intentioned, high-stake, high-pressure tactics by friends, families, or professionals are not evidence-based and may also cause more harm than good. The producers of Scared Straight claimed success with their cohort, but a 2013 analysis of this type of program showed an increase in delinquent behavior instead, leading the authors to conclude that “we cannot recommend this program as a crime prevention strategy.”

Likewise, while “tough love” tactics may be necessary (for example, barring a family member who has exposed young children to an unsecured drug supply from a home), they should be understood as benefiting the family but not necessarily the person suffering from substance dependence.

Myth #3: People with substance use disorders are irrational.

The myth: Substance use causes people to become crazed beings that are incapable of following logic or making decisions for themselves. As far back as the 1930s, films about “reefer madness” portrayed cannabis users as unhinged and murderous. Since then, drug users have been routinely described using the imagery of demonic possession and superhuman strength in an attempt to justify police force against drug users, a perception that has been glorified in the show Cops for over 30 years.

Rhetoric in the 1980s referred to drug-using urban youths as “superpredators” without capacity for remorse or compassion. When a “bath salt” variant called flakka came on the scene a few years ago, media referred to it as the “zombie cannibal drug” based on a couple of unusual events that did not reflect overall use.

More recently, the “Free Britney Spears” movement has recognized the extreme case of a celebrity placed under legal conservatorship (where her father controls her assets and personal freedom) after a substance-related mental health breakdown in 2008 that remains in place well over a decade later.

The Spears case is a fascinating look at the crossroads between disability, self-determination, and the rights of people who use (or have used) substances to be recognized as full human beings and control their own destiny.

The truth: By definition, substance use disorders include a withdrawal state when the substance is stopped, which can drastically shift the focus of a person’s needs and priorities. Far from “wanting to just get high,” the problematic behaviors seen in people with substance use disorder are largely related to avoiding withdrawal.

Withdrawal from opioids, for example, can be so profoundly unpleasant (combining the worst symptoms of conditions like the flu, gastroenteritis, and panic attacks), that people may sacrifice critical life activities such as child care, work, and engagement with family in order to obtain the drugs that stave off withdrawal. In fact, impairment of various key life activities makes up nearly half of the criteria for opioid use disorder according to the DSM5.

In understanding behaviors around substance use, it can be useful to presume that most human behavior is essentially rational – that is, that people are following the most sensical pathway presented to their mind in whatever state the mind finds itself.

Even when drugs like hallucinogens alter sensory perceptions, a person generally reacts in the most logical way they can – enjoying pleasant imagery or attempting to escape from frightening visions. When a person is faced with the profoundly unpleasant possibility of withdrawal from opioids (or the life-threatening possibility of withdrawal from benzodiazepines), it becomes logical that they may prioritize obtaining and taking drugs even at the expense of key life activities.

For the person facing withdrawal, seeking relief from this condition may be the most logical pathway they can see to staying engaged with work, school, or family life.

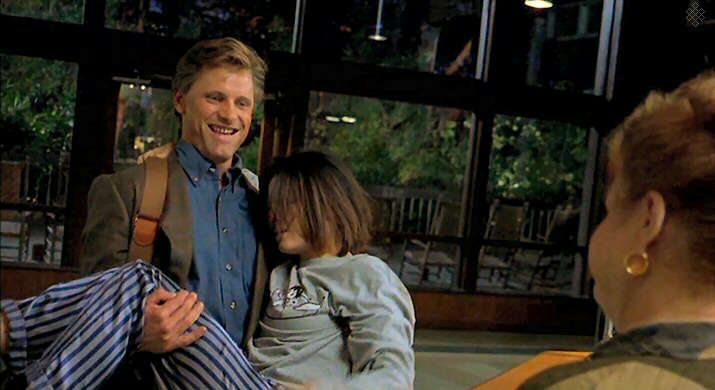

Dr. Gabor Mate

Myth #4: Trauma is the only path to addiction.

The myth: People with substance use disorders are invariably victims of severe trauma that drive them to numb emotions and escape reality. Dr. Gabor Mate, a well-respected addiction specialist, has stated that “all addictions are attempts to escape the deep pain of the hurt child,” and “the urge to escape pain shared by all addicts.”

The truth: People come to substance use disorders through a variety of pathways, including recreational overuse, poorly managed treatment for chronic pain, and problematic life circumstances that make drugs an attractive alternative to feeling difficult emotions. Genetic vulnerability also plays a role in determining who is more likely to go onto opioid use disorder from casual or short-term use.

While trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are crucial to explore as recovery begins, the emphasis on trauma as a singular pathway to addiction can alienate individuals from seeking treatment if their experience does not fit that narrative.

A patient once told me that she wished she had some kind of trauma in her past to justify her opioid problem; the lack of any explanatory trauma left her feeling more shamed, as she felt she could not explain dependence that started with simply liking the energy she got from opioids, then taking enough to become dependent. In the end, no matter how individuals arrive at substance dependence, everyone deserves the standard-of-care treatment that best meets them in their current circumstance.

Myth #5: People immediately become addicted after only one use.

The myth: Some substances are so powerfully addictive that one use dooms a person to hopeless dependence. “Moral panic” invokes such over-exaggerations and is routinely resurrected about new drugs or drug classes that arise over time.

PBS’s America Addicted series invoked this falsehood in a 2017 documentary segment that was partially filmed at the rural community health center where I worked at the time; after a clip invoking patient-centered approaches to recovery and relapse, the scene next switched over to a law enforcement officer who reiterated the tired myth about heroin users that “once they use it, it’s like it takes control of them.”

The truth: Addiction is a learned behavior involving predictable rewards in response to repeated stimuli. While individuals may greatly enjoy a substance and desire to take it again, repeated regular doses are required to alter the body’s basic equilibrium to the extent that a person feels true withdrawal if they miss a customary dose.

In Maia Szalavitz’s groundbreaking book Unbroken Brain, she describes addiction as a learning disorder wherein maladaptive patterns become learned through repeated reinforcement – not profound alteration through a single exposure.

Columbia neuroscientist Carl Hart questions the true addictiveness of even hard drugs like cocaine in his book High Price, which reviews studies that show that many people can maintain casual use without dependence and even those dependent on some substances can make moment-to-moment choices about drug use when offered other rewarding alternatives.

Conclusion:

These media myths (along with many others) can create barriers between opioid-dependent people and their pathways to recovery. However, these tropes are not universal, and accurate depictions of drug use and recovery are available. Whether one sees their experience reflected in the media or not, popular perception of drug use should not stop individuals from seeking the care they deserve to address their challenges with substance use.

To learn more about the success rates and safety of Bicycle Health’s telemedicine addiction treatment in comparison to other common treatment options, call us at (844) 943-2514 or schedule an appointment here.