https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LH7TXPV_uxY

Genre: Documentary

Director: Charlie Siskel (co-director of “Finding Vivian Maier”)

Runtime: 80 minutes

@ the Chicago International Film Festival

Documentary filmmaker Charlie Siskel (nephew of Gene) has a new documentary set to be released in March that should earn him an Academy Award nomination, just as his work on “Finding Vivian Maier” did. Speaking to viewers at the Chicago International Film Festival on Saturday, Oct. 15, Siskel, who was a field producer on “Bowling for Columbine” in 2002, told the audience that this was only the third time showing the film. (It premiered at the Venice Film Festival August 31st and then showed at the Hampton Film Festival.)

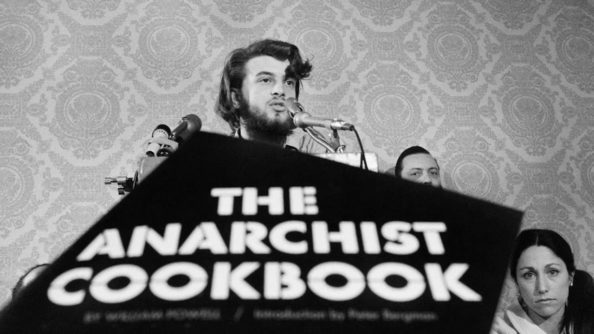

Chicago, Siskel’s hometown, is the third stop on what promises to be a seriously star-studded series of laudatory appearances for the intriguing and thought-provoking documentary about William Powell, the man who wrote 1970’s The Anarchist Cookbook. As the program notes say, the 80-minute documentary is “a captivating portrait of William Powell, who, at 19, authored the infamous militant manifesto The Anarchist Cookbook. Now an educator in his sixties, Powell is deeply haunted by his own creation. A cautionary tale of rebellion and its unintended consequences.” An Oscar-nomination is a foregone conclusion after viewing this impressive but controversial documentary.

Following the showing of the film, Siskel admitted to his great admiration for the documentary films of Errol Morris. The method he employs (off screen questions from the filmmaker) is very reminiscent of Morris in documentaries like “The Known Unknown” or “The Fog of War” and, also, those of Michael Moore, with whom Siskel worked on “Bowling for Columbine.”

Siskel began the William Powell interview by suggesting, “The book, as I read it, advocated the violent overthrow of the United States government.

Powell immediately objected to that conclusion until reading from his own book, line by line (“I haven’t read it since I wrote it.”) confirmed that it is a book for anarchists espousing violent solutions to problems and “not a book for children or morons.” Powell still maintained, “I don’t think the book actually tells you what to do with this information.” Siskel then had him read these lines from the book: “There is only one choice for a real man, and that is revolution.” That quickly quelled Powell’s objections.

As the film progresses, it becomes increasingly clear with passages like “Freedom is based on respect. Respect is earned by the spilling of blood” that Powell’s objections aren’t standing up to scrutiny. He reluctantly admits, “I can see that people might read portions of the book and find justification for doing very evil and violent things. And that fills me with remorse, which is different than regret.”

If you had the quick thought, “What IS the dictionary difference of remorse versus regret?” let me refresh your memory using Webster’s New World Dictionary. Remorse, says Webster, is “a torturing sense of guilt for one’s actions.” Regret is “to feel sorry about one’s actions; to have remorse, especially over one’s acts or omissions.” One word defines the other. Synonyms, if you will. [It reminded me of Bill Clinton’s parsing the English language when he was interrogated during the Monica Lewinsky scandal.]

Siskel continued asking probing questions of Bill and his wife, Ochan Powell. It is evident that Powell has suffered because of his adolescent rebellious period, but so have many others, as is pointed out to him by Siskel in the process of bringing up the many shootings, bombings and terrorist acts where The Anarchist Cookbook was implicated. It was the Bible that terrorists or troubled adolescents used to make bombs and other weapons. (Powell’s defense is largely that he didn’t know about all of this because he was not living in the United States at the time. He adds, “Part of the fact that I don’t know is that I don’t want to know.”)

Siskel told a fascinated audience (that didn’t want to leave the theater), “I really was interested in the human story. I imagined that the book must have taken a toll on him. I wanted to present a picture of him that was fair.” When I asked how Siskel managed to get Powell to do the piece, when Powell had turned down Charlie Rose, the BBC, and a host of others, the answer was, “My timing was right. Powell was 65. In poor health. Working on a memoir. He appreciated my willingness to create a fair and balanced point-of-view.”

Siskel says, “He (Powell) both wanted to talk about the book and there was a certain cast he wanted to put on his own story.” He commented that Powell’s son was involved in the project and shared family photos. Siskel spent a week at the Powell house in France. Said Siskel: “The relationship I had with Bill was complicated. He passed away a month before the film was finished (July, 2016). I’d like to think that the portrait is a very sensitive one. I hope that, in the end, the message is a sympathetic one. His youthful mistakes played out in such a public way. Some audiences do not sympathize with him, but an equal number feel he redeemed himself by the choices he made in his adult life.”

The mature Powell devoted his life to working with students all over the world with learning disabilities, students who are alienated and disenfranchised. Powell says that perhaps he feels most at home anywhere where he is an outsider.

Young William Powell was just such an alienated student. His father was a United Nations spokesman for the Attorney General and the family moved to the United Kingdom when Bill was two. He was an outcast in a British system described as “a miserable school motivated by fear.”

Young William Powell was just such an alienated student. His father was a United Nations spokesman for the Attorney General and the family moved to the United Kingdom when Bill was two. He was an outcast in a British system described as “a miserable school motivated by fear.”

When he was 12, the family moved back to New York and young William again was regarded as an outsider in his native land, especially since he now spoke with a British accent. Bill knew nothing of the culture he was suddenly thrust into and didn’t fit in, constantly cutting class and getting into trouble to the point of expulsion. His parents ultimately sent him to Storm King School, “a school for rich delinquent children.”

From there, coming of age in the turbulent late sixties (Powell wrote the book in 1969 and it was published in 1970) the young man thought he was living in an Apocalyptic world. When alone with a typewriter, he wrote down his thoughts about taking violent action, expressing them in a confident tone (he has twice publicly disavowed the views expressed in the book written when he was 19) because, he says, “I was a 19-year-old who hadn’t thought about it. You come to believe what you’re writing.”

Did he do enough to stop publication of the book? Did he do enough to disavow his youthfully naïve expressions of rebellion? Did he cash $40,000 to $50,000 in royalties that the book earned over the years and take the $10,000 pay-out offered by the book’s publisher as the publisher was going out of business ?

Powell was conflicted to the very end of his life, (July of 2016). He did not live to see the finished documentary or to finish his memoir. His widow, Ochan Powell, has not yet viewed the film. Director Siskel said, “He (Powell) was not able to just run with a topic. He couldn’t come clean or admit certain things without some provocation” and quoted Powell’s wife saying, “You being here has caused us to take stock.” Siskel referenced ”certain roadblocks” that Powell would throw up around their discussion(s), adding, “My interest was not in finding any sort of responsibility or making any judgment. He was a flawed subject—we all are.”

Powell talks about his second book, The First Casualty. The book focused on the assassin who started World War I in 1914 by assassinating the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Warming to the topic of his second book, Powell says, “The book was told from the point-of-view of the assassin. He had the courage of his convictions and he acted on them.”

Siskel immediately challenges Powell, asking if he sees the parallels with his own life. Powell gives a puzzled, tortured look and, again, acts as though he can’t or won’t see the connection. Siskel: “There is a lack of self-awareness in that last beat.” Powell repeats throughout, “While I do feel responsible, I didn’t do it.”

A first-class Oscar-worthy documentary.