Paul Greengrass, the U.K. filmmaker responsible for such gritty slices of realism, as “Captain Phillips”(2013), “Bloody Sunday” (2002), “Flight 93 and the Bourne films came to the Chicago AMC Theater on Monday, October 1, in support of his Netflix film “22 July,” which focuses on the Norwegian massacre of 77 people—-mostly adolescents—that took place on July 22, 2011 in Oslo and the nearby youth camp at Utoya Island.

The film runs a lengthy 2 hours and 13 minutes, but it is scheduled to be shown on Netflix beginning October 10th. It is being given a big push in regular theaters, showing in over 100 of them, a new Netflix concept. The $20 million dollar film shot in Vestfold, Norway, is based on the book “One of Us” by Asne Seierstad; Sieerstad shares a screenplay credit with Greengrass.

The film is a searing look at the far-right shooter (Anders Behring Breiviak) who gunned down 77 innocent people on July 22, 2011, and an implied warning for the world that such violence is not going to be confined to Europe in the coming months and years. As the shooter, Anders Behring Breivik said before he opened fire on the unarmed children huddled together in a campground building, “Marxists, liberals, members of the elite: you will die today.” At trial, Breiviak said he was a member of a secret group (Knights Templar) intent on reclaiming his homeland for white supremacists and “Tomorrow is going to belong to us.”

The Prime Minister in a meeting with his aides during a conference following the shooting is advised, “A war is coming,” to which Jean Stoltenberg (now Secretary General of the United Nations) replies, “I’d say the war has already begun. The stormfront is joining up with Europe.”

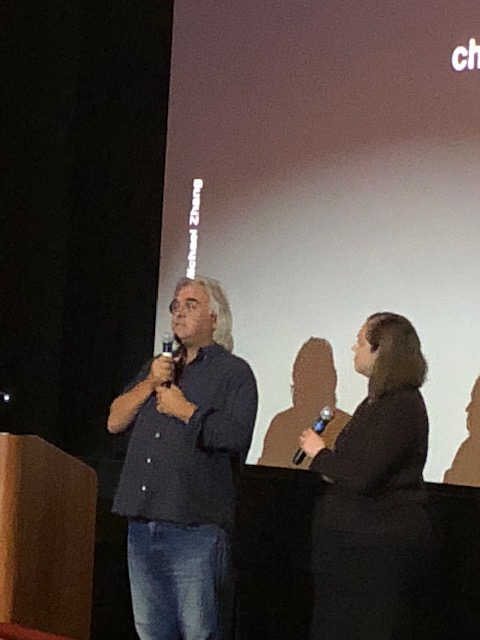

Paul Greengrass with CIFF Director Mimi Plauche on October 1 in Chicago. (Photo by Connie Wilson)

Sixty-nine of the students at the AUF Labor Party camp died, over 200 were wounded, and 8 more people died at the site of a truck bomb explosion that Breivik detonated around 3:30 in the afternoon outside the Prime Minster’s office, before driving the 40 kilometers to Utoya Island, where he systematically began the slaughter of 69 teenagers, attired in a bulletproof vest that mis- identified him as a policeman.

Before he began his killing spree, Breivik published a manifesto in which he said, “Consider this my gift to all Europeans.” During his subsequent trial, he called his actions “A war to take back control of Norway.” When called upon to testify in court, Breivik first stood and gave the Nazi salute, enraging the parents of the slaughtered innocents who were present in the specially-constructed courtroom.

Said Breivik: “This is a war. Attacks can come at any minute…I speak on behalf of Europeans who have been denied their indigenous and cultural and territorial rights. These are not real democracies, or else we shouldn’t be forced to accept multi-culturalism. When peaceful revolution is denied, then violence becomes inevitable. I fight on behalf of my country.”

The main action (i.e., the massacre) occurs during the first half hour of the film, and the subsequent hour and a half is devoted to trying to determine who this man was and why he committed this heinous crime. The film views the proceedings through the eyes of one of the most badly wounded of the students as he struggles to recover. The “normal” citizens are represented by many survivors who are invited to present testimony at trial, especially the young teenaged boy named Viljar, (well-played by Jonas Strand Grovli,) who must overcome being shot 5 times and confront the assassin in court.

As the film documented the dysfunctional childhood and family that spawned the shooter, a picture of a loner who is not “paranoid schizophrenic,” (as the court psychiatrists originally reported), but, instead, a cold-blooded killer who wanted to strike at what the leaders of Norway held most dear—their children—in order to gain maximum impact. Brievik is very insistent upon being given a bully pulpit in the courtroom; he promises not to appeal his sentence if he is allowed to speak. (A documentary by Michael Moore’s “Where to Invade Next” (2015) took us to the prison on an island that becomes Brievik’s home for the rest of his life in solitary confinement; it resembled a Thoreau-like cottage in the woods.)

Much like Michael Moore’s documentary “Fahrenheit 11/9” and Spike Lee’s “BlackKKlansman” all three recent films are urging complacent citizens who are, at best, lacksadaisacal about voting, to WAKE UP! This film warns that an organization calling itself Knights Templar (formed after 9/11) that says it wants Islam out of Europe and will stop at nothing to achieve that goal, is growing in power with Brexit and Trump’s ascension to the presidency. At the very least, the populace of the U.S. has been pitted, one citizen against another, in a fashion reminiscent of North against South in the 1860s.

In some ways, the North against South battle lines fought during the United States Civil War is not an incorrect analogy, as Trump voters who were enlisted by Donald J. Trump and have become his “base” were largely from fly-over territory ( the South and Midwest). Their complaints echo those the shooter in this film articulates, with some distinctly American twists involving jobs leaving the U.S. and America losing its Premiere position on the world stage. The Norwegian shooter who vowed “We’re deadly serious about seizing control by any means necessary” would have been right at home in Charlottesville.

The Prime Minister of Norway (now Secretary General of the United Nations), Jens Stoltenberg, said, “We must not give in to this terror, but we must not be changed. Fight with rule of law, not with the barrel of a gun.” Greengrass acknowledged that “Norway had to distill a complex legal process to explain who this individual was and why he did what he did. In the end, they came to the consensus that he was not crazy. Plain truth that had to be faced: he was a dedicated, violent, right-wing, neo-Nazi home-grown terrorist. It was a very uncomfortable thing for Norway to face up to.”

In a Q&A following the film, Writer/Director Paul Greengrass said he was “holding a mirror up and showing the world how it’s going.” He noted, “These events are meant to weaken our trust in one another and in our institutions.”

Greengrass also said he wanted to show how direct involvement in the violence affects the survivors. “Later, those of us not directly involved get to go on with our lives. For those caught up in it, it doesn’t go away. This particular group sees the rise of a new right-wing movement in Europe and beyond Europe.” He asserted, again, that it was “important that there are films that look at how we are in these turbulent unmoored times and hold up a mirror.”

When asked why he chose this subject for his next film, he said, “What attracted me to this story is that it was the story of how Norway fought back.”

In conversation with Cinema Chicago staffer Anthony Kauffman after the film, Greengrass was asked how he happened to choose this topic? (Q1)

Paul Greengrass (“Captain Phillips,” “22 July”) with Anthony Kauffman.(Photo by Connie Wilson)

His answer (A1): “I went to Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg first, to see if I could ask the families’ for permission to tell their story. I figured I’d get a politician’s read first. He was very positive, saying, ‘You need to make this film. It’s a big threat, and it’s rising fast.’ People—the families—wanted us to make this film. That’s when you know it’s right.” Greengrass said that many of the teenagers in the camp shooting scenes had known someone who was there, and that, in a country with a population as sparse as Norway’s “pretty much everyone in Norway knew someone who was involved.”

Q2: Did you go meet Andres Behring Breiviak?

A2: “I did not meet the villain. I didn’t want to dignify his narcissism by getting in touch with him.” (Anders Behring Breivik, the assassin, is brilliantly played by Anders Danielsen Lie.)

When asked why he didn’t include a post-film coda of the real survivors and the victims on whom the roles were based, Greengrass said that he prefers not to do so, but that “probably all the real characters would have been happy to do it,” adding, “I like to keep the integrity of the film. I like the aesthetic to be as simple, as stripped-back as possible.” Much like the Somalian pirates in “Captain Phillips,” the shooter is portrayed in great depth, rather than as a cardboard cut-out of evil.

Q3: How do you push actors to make them seem real?

A3: “Every filmmaker has a tentpole. For me, I’m drawn in by real life. I always encourage the actors not to act, but to explore the moment.”

Q4: What made you choose the young boy Viljar who was shot 5 times as the individual through whose eyes we see the action?

A4: “So many people remembered his testimony at trial. He was one of the few who got a reaction from the assassin. In the end, you’re trying to make his story represent all of their stories.”

It was noted at film’s end that Viljar has continued with his schooling at University and intends to go into politics, following in his mother’s footsteps, as she was the Mayor of a small Norwegian town. “22 July” will air on Netflix beginning October 10th, 2018.