Esmarelda’s Summer Seventies Series

What if the most important filmmakers of all time snuck subliminal messages into their films for one person to decipher fifty years into the future? That sounds like the plot of a pretty cool movie, doesn’t it? Anyone who has taken an Introduction to Film course at even the smallest community college should have an idea of exactly what is meant by The New Hollywood movement; but today, as film, television, and entertainment all become increasingly more fragmented, I often ponder if we don’t intellectually reference New Hollywood as simply a highlight of film history as opposed to the origin story of prognostication from some of the most renowned, revered, and influential filmmakers both since passed and still working today.

A few years back, I began to immerse myself in the old. I revisited many of The New Hollywood films I had watched back in film school, but dove headfirst into several others that, for whatever reason, were deemed unworthy to make cameos in the standard textbooks. But through all of this viewing of both the known and unknown, I began to see one very interesting, very telling, very similar pattern – and that is that any single one of those films could easily have been made and produced today.

There is much discussion lately about film as a form of social justice. The need to push out the old fogeys in favor of new voices, and the critical importance of championing films that make a statement about mental health, police brutality, gender identity, political corruption, and women’s empowerment. The fact of the matter is that any if not all of these topics were already explored a full fifty years before we started hashtagging about them. Many were recognized by the Academy Awards, several were huge financial successes, and nearly all of them were made by the exact same “old fogeys” that are being pushed out of the way in favor of new voices lifted up by social media each day.

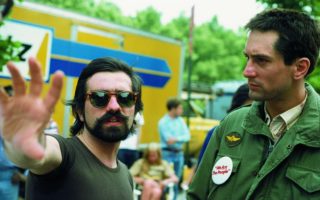

There would be no “Joker” without “Taxi Driver.” “Dog Day Afternoon” introduced a transexual character to mainstream audiences with both care and consideration, free from any hackneyed stereotypes. In the seventies, the term “independent film” held more weight than simply a genre or financing model, as those who made films sought to make those films come hell or high water, without asking anyone for permission or a helping hand. The term “true indie spirit” has been watered down to reference a film that has a personal connection to its filmmaker as opposed to the gung-ho, do-or-die, boundary-pushing craftsmanship by which indie films of the 1970s were made.

The year 1967 ignited a real turning point in film history that signaled a change in how films were made for the decade that followed. Sex, violence, action, and a general distrust of authority permeated the big screen in a way that audiences had never seen – or been allowed to see – before. Special effects were made by hand, stunt men were the studs of the town and aside from the angry mothers wagging their fingers, most audiences could recognize and understand that the bloody violence created on screen was made up of food dye and cornstarch. But true film lovers didn’t care. Repeated viewings were commonplace and if you liked a film, you went back and watched it more than once and told all of the kids in school about it the following Monday morning at recess. Finally, in nearly fifty years of cinema, we had entered an era where the images on the big screen were a direct reflection of the world as it actually was – corrupt, dirty, sexy, fragile, and heading in a direction that, without art, might spell the end of extrasensory communication as we know it.

I am a strict believer in caring more about how a film is crafted than what it is about. A premise, subject, or genre rarely interests me as much as a filmmaker itself. But this is because I am attracted to what it is that a filmmaker is attempting to say. I am drawn to another individual’s perspective on the world, and whether or not the director, coupled with the screenwriter, is able to form opinions on hot-button topics that I might not otherwise be conscious of. I want a film to grab me without giving me an excuse to look away – I want to have a conversation with someone about the twists and turns and surprises I didn’t see coming. I want the playing field to be even. It doesn’t matter to me who is behind the lens or on the screen: I want to know how entertaining, captivating, and memorable each frame of those 80-150 minutes is. Because that is the craft of filmmaking: a painter has a canvas, a sculptor has a piece of wood or clay, but a filmmaker has a finite amount of time by which they seek to craft their vision. It is my belief that the best artists – the ones whose work we travel thousands of miles to see – are the ones who are able to execute their vision of self-expression in such that, without guidance or prompt, an astute observer is able to see past the markings on the page to the core of the artist’s own truth.

Truth is a feeling. Truth is a musical note. And The Seventies, as a period of film history, is held in such high esteem because embedded in the celluloid frames of those moving images are, at its core, brutally honest expressions of truth. An artist has its canvas, a sculptor has its clay, and a filmmaker is responsible for crafting the manipulation of time through dialogue, images, and emotion in order to communicate an idea to another individual without direct physical interaction. Filmmaking, at its core, is the highest form of telepathy and throughout this series, I hope to convince you that the “old fogeys” you learned about in your Introduction to Film course might, in all actuality, be the greatest living Jedi Masters walking the earth today.

Please enjoy our Summer Seventies Series.